The Urgency of Reopening Schools

A World Bank study estimates a loss of 0.3 to 0.9 years of schooling. The repercussions of learning loss and increased dropout rates are also likely to diminish the economic opportunities for this generation of students. How have countries responded to these challenges? Do they appreciate the sense of urgency that is required to rise to the challenge?

- UNICEF: Rosmarie Jah, Oscar Onam, Noguebzanga Jean Luc Yameogo

The cost of school closure

On September 16, 2021, UNICEF estimated that worldwide children lost 1.8 trillion hours of in-class instruction over an 18-month period since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. School closures and the lost hours of instruction translate to about 206,000,000 years of missed learning. 58.8 million children and youth (3.4 percent of all learners) in 14 countries worldwide are yet to resume in-person schooling due to ongoing national school closures.

One big concern is whether these countries, and many others that shut down schools for extended periods, will be able to recover from the learning and human capital loss. Especially students that live in poverty and do not benefit from remote learning opportunities, are less likely to come back to school when they eventually reopen – particularly those that were at risk of dropping out before COVID-19 hit. Children and youth who will come back to school are likely to suffer from an erosion of previously acquired academic knowledge and skills. In addition, they will also be at a higher risk of repeating especially if they are in exam years, or the last grade in primary or secondary school. Even for students in countries that resorted to distance learning modalities via digital platforms, there are concerns that they did not acquire knowledge and skills at the rate they typically would have during regular in-person teaching in school.

On future economic and education impact of the school closures, a World Bank study estimates a loss of 0.3 to 0.9 years of schooling (adjusted for quality), bringing down the effective years of basic schooling of children and youth from 7.9 years to 7.0 or 7.6 years respectively. The repercussions of learning loss and increased dropout rates are also likely to diminish the economic opportunities for this generation of students who stand to lose an estimated USD 10 trillion in earning, or almost 10 percent of global GDP, which amounts to one-tenth of global GDP.

So how have countries responded to these challenges? And do they appreciate the sense of urgency that is required to rise to the challenge?

How are countries currently providing education?

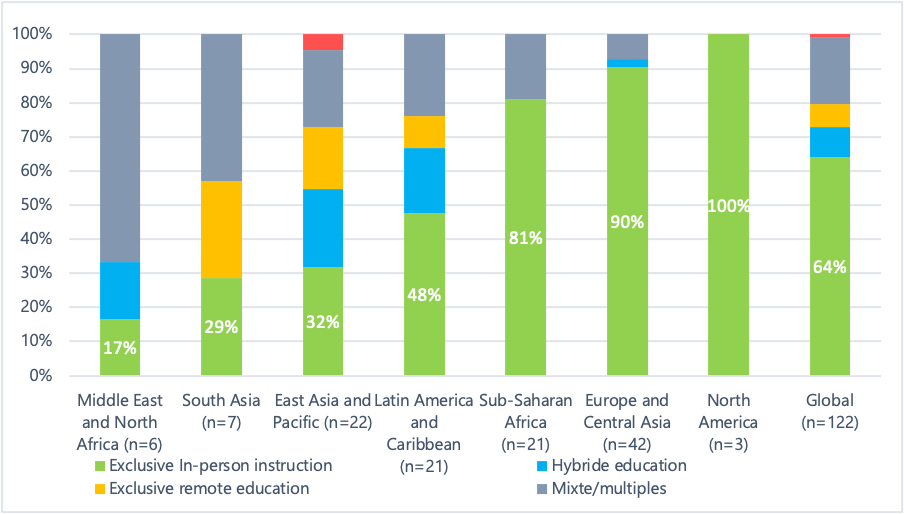

The response of education systems to COVID-19 globally was still diverse by September 2021. A few countries had resorted to a long-term complete shutdown of schools without providing any learning alternative for students. While the majority either continued with in-person teaching in schools or adopted a hybrid model that combined in-person learning with distance courses or remote teaching exclusively. In some countries, a combination of these approaches was used, and it varied based on education level, type of school, or the region in the country. Recent data from the Global Education Recovery Tracker (see figure 1) shows that two out of three countries had resumed full-time in-person teaching for primary and secondary students, while in one in five countries at least two of the above teaching modalities were used concurrently.

There were significant disparities between regions. In Asia and North Africa, only a small proportion (less than a third) of countries had resumed in-person teaching for all primary and secondary students, whereas in sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, and North America, more than 80% of countries had already reopened primary and secondary schools for in-person learning.

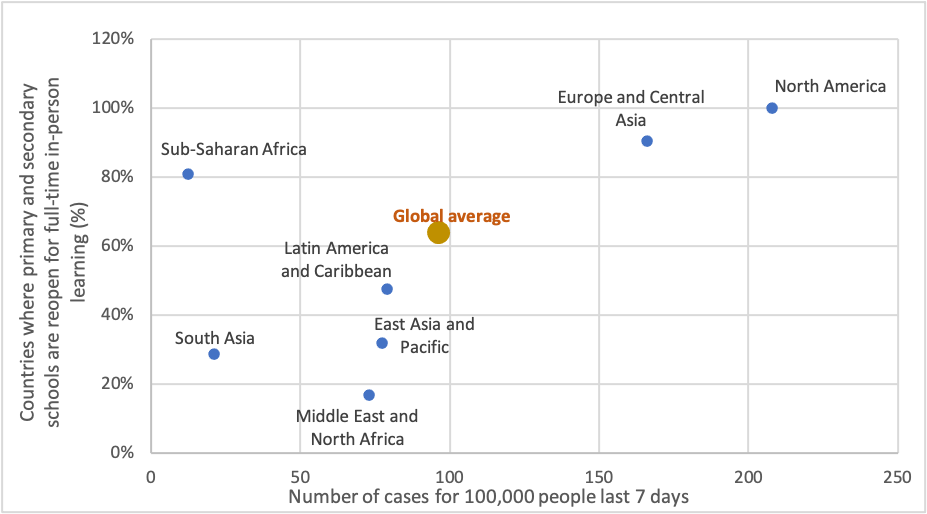

A comparison of COVID-19 community transmission - measured by the number of new cases in the last 7 days (from 8 October 2021) - with the situation in schools (see figure 2) shows that the regions with the least number of new cases were not necessarily those where most countries had resumed in-person teaching. The regions of Asia and North Africa had fewer cases than North America and Europe in proportion to their populations, yet the countries in these regions had not yet returned to full-time face-to-face teaching for all students. Similarly, community transmission in sub-Saharan Africa was comparable to that in Asia and yet about 80% of African countries had reopened primary and secondary schools for in-person learning. Only 29% of countries in South Asia had resumed in-person learning.

School/education status for primary and secondary students, by World Bank region

Number of new cases for 100,000 people in the last 7 days and school/education status for primary and secondary students

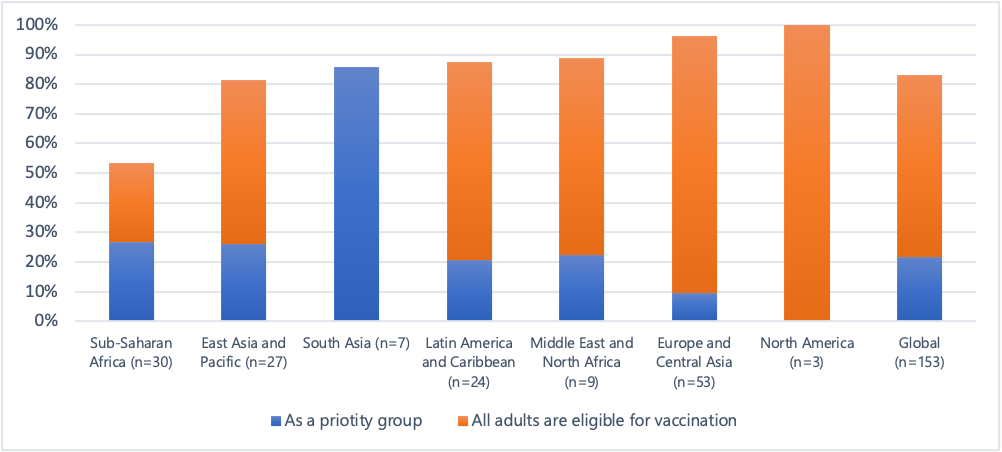

Regarding vaccination, in most countries (80%) teachers are being offered the opportunity to be vaccinated (see figure 3), either as a priority group or because there are enough doses to meet the demand. A comparison by region shows the particularity of sub-Saharan Africa with only 54% of countries offering the possibility to teachers to be vaccinated while in other regions this percentage varies from 81% in East Asia and Pacific to 100% in North America.

Percentage countries where teachers and other school staff are being offered vaccine

The pandemic’s silver lining in education

The struggle to ensure continuity in learning during school closures globally necessitated innovations in digital solutions in several countries. Digital solutions have proven to be effective when accessible, used appropriately and deployed equitably: They allow to expand classroom boundaries to reach more children in far-flung corners of a country, facilitate teacher training and personalizing learning; provide learning opportunities for children with disabilities through assistive technology, engage parents with regular information on their children’s schooling. Millions of teachers stepped up and adapted. They learnt new teaching techniques and classroom routines, in the process increasing their proficiency in technology-supported teaching.

Existing disparities pre-pandemic exacerbated and exposed

While educators have worked harder than ever during the pandemic, it has not all been sunshine and flowers, especially regarding the use of digital solutions to facilitate remote learning. For starters, all education systems, in rich and poor countries alike, were not prepared to offer high-quality remote instruction. Second, the digital divide that existed before the pandemic was exposed and some inequalities were reinforced. Poorer countries and households struggled the most with internet connectivity as they bore the brunt of the closure. More than half of the world’s children and young people have been found to be on the wrong side of the divide. UNICEF data shows that at least for 463 million children whose schools closed during COVID-19, there was no remote learning. The biggest share of these students was and still is in sub-Saharan Africa. Rural communities including the urban poor, continued to lack reliable, affordable internet access. The gaps in school participation and learning achievements between children from rich and poor households/countries, and boys and girls, have widened, particularly in STEM subjects. If schools are not opened as soon as possible for full-time in-person learning, we run the risk of reversing pre-pandemic gains on equitable access and learning outcomes.

Will reopening schools for in-person learning lead to a spike in COVID-19 cases in the communities?

Whether reopening schools for full-time in-person learning will spike up cases of COVID-19 is a critical question, especially with the highly transmissible delta variant of the SARS-Cov-2 that is currently driving the numbers of new cases in every country. While evidence continues to emerge regarding the effects of in-person schooling on community COVID-19 transmission risks, current studies suggest that in-person schooling does not appear to be the main driver of infection spikes when appropriate risk mitigation strategies are in place. When multiple mitigation measures are consistently and correctly used, child-to-child or child-to-adult transmission within schools is found to be relatively rare. Studies have found that transmission rates during in-person learning mirror that of the surrounding community, suggesting that efforts to reduce transmission to protect teachers, staff, and students while in school should focus on controlling the spread in the community.

What reopening schools should look like?

How can we at national and school levels quickly adjust to the new normal in the COVID-19 era? Countries, especially those in the low-income group, need to proportionately adjust their education budgets and adapt a cross-sectoral investment approach to finance the recovery efforts from the learning losses and other challenges due to COVID-19. Investments in remedial education are required, alongside prioritizing teacher vaccination, physical distancing by reducing class- or cohort-sizes, improving ventilation and water sanitation and hygiene facilities in schools, and promoting compliance to hand hygiene and masks guidelines. These recovery efforts should be seen as public health measures and investments in human capital in terms of saving and/or increasing this generation’s future earnings, economic productivity, and social returns (i.e., intergenerational social mobility, civic literacy etc.)

Making the decision to reopen school

The cost of inaction is high, and we cannot afford to let children and young people become the ‘COVID generation’ and bear the brunt of this pandemic. Education is key to recovery – including economic recovery. Children and young people need to be able to resume in-person schooling as soon as possible. When they return to schools, they must be offered a full range of remedial and support services, including complimentary world-class digital learning, with teachers given resources to empower them to support children’s needs holistically and bring them back on track.

Many governments face the challenge of coming to acceptable, and safe decisions on when and how to reopen schools. The decision to reopen schools has many implications for children and other stakeholders in terms of health, learning, equity, social protection, mental health as well as long-term considerations for a country’s human capital development. The trade-offs are especially severe for the most vulnerable children including girls and children living in poverty.

Given the uniqueness of each context, no one size fits all approaches can be applied. However, ethical considerations can guide the decision-making process and help evaluate the trade-offs. Hawk et al. suggest applying an ethical reasoning strategy with eight key questions evolving around (1) fairness, (2) outcomes, (3) responsibilities, (4) character, (5) liberty, (6) empathy, (7) authority and (8) rights.

To come to a fair decision, for example, it is necessary to analyze the impact on the most vulnerable. For instance, employing remote learning can disproportionally benefit children from a strong economic background whilst poor children living in resource-constrained environments risk being left out. Questions around legitimate authority examine whether reopening or delaying reopening schools conflicts with international, national, and local laws and norms. In terms of understanding what rights apply when deciding on the reopening of schools, fundamental rights such as the right to life, education and to health are considered.

The aim of the ethical reasoning strategy is to arrive at well-informed decisions, and it helps to protect against superficial polarization of opinions in times of crisis. The application is not simple, but it allows for quality decisions made in the best interest of children and society.

About the authors

- Rosmarie Jah is an Education Specialist and the lead for Advocacy and Partnerships for UNICEF’s HQ education team in New York, USA.

- Oscar Onam is an Education Specialist in UNICEF’s HQ education team in New York, USA.

- Noguebzanga Jean Luc Yameogo is an Education Specialist in UNICEF’s HQ education team in New York, USA.

Disclaimer

The ideas and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNICEF, the World Bank and JHU and do not commit the organizations or their respective member countries